Partner Spotlight: Japanese sukumo with Makiko-san

“Indigo is my master – it teaches me how to live with nature, leading me down a path of chance encounters that connect me with others who are equally fascinated and curious about indigo and shibori.”

-Makiko San

Student hands at Makiko-san’s studio.

Considered the oldest natural material to color cloth, in Japan, indigo was once a color closely associated with samurai warriors, who were often dressed head to toe in indigo-dyed garments and armor. The color was believed to offer protection and was deeply intertwined with superstition. It was commonly referred to as “kachi” in Japanese, a word that also means “to win,” upholding the idea that a warrior dressed in indigo was clothed in luck and fortune. What’s more, with indigo’s natural antiseptic properties, it made a good option for warriors to clothe themselves.

Across Japan today, Japanese indigo (Persicaria tinctoria) is still revered. While its symbolic meaning has shifted, it is now a plant that is intertwined with valuing deep respect for craftsmanship and nature, a mindset that continues to travel far beyond Japan through the global appreciation of indigo dyeing.

Indigo is a plant that requires warmth and moist soil to thrive, with temperatures above 50°F considered ideal - making Japan an apt part of the world for the plant to grow. Farmers typically harvest indigo two to three times during the growing season.

Successful cultivation, however, depends on well-timed harvesting, as the plant reaches peak dye potential only at certain stages. Indican, the precursor to indigo pigment, is found almost exclusively in the leaves, particularly in younger growth, the concentration of the dye fluctuates throughout the plant’s life cycle, thus regular, consistent small harvests of the leaves throughout the plants life allow for optimum plant health and indigo dye. Developing this understanding takes time, experience, and a close connection with the plant.

Buaisou team planting young indigo plants in the field.

In Japan, indigo dyeing (aizome) has a long legacy in many regions, but Tokushima is especially renowned for its high-quality sukumo (fermented indigo leaves). The indigo of this region, called Awa-ai, became a dominant product in the Edo period and was widely traded across the country, bringing economic and cultural influence to Tokushima.

The art of making sukumo – fermenting and composting indigo leaves – was refined over generations. Tokushima’s climate, traditional techniques, and careful craftsmanship helped establish its reputation for some of the best natural indigo dye in Japan.

Formerly the Awa Province, Tokushima is a contrast of old and new, reflecting traditional Japanese nostalgia through its Edo-period heritage, while simultaneously embracing modern life. Geographically, it is an area characterized by flat, low-lying, fertile land and a humid climate that is ideal for indigo cultivation. The Yoshino River basin, in particular, played a key role. Frequent summer rains and typhoons often caused flooding that made rice farming difficult, whereas indigo could be harvested before the typhoon season. Periodic floods also helped replenish the soil with river sediment, further supporting indigo growth.

Watanabe-san’s young indigo plants growing strong.

While the river is now leveed and organic fertilizers are added in place of the river sediment, Tokushima remains an thriving center for indigo farming and practice, with artisans continuing to keep the tradition alive. More recently developed as an industrial region, Tokushima has long valued labor-intensive, hand-based skills, like the practice of indigo dyeing. In Tokushima, indigo continues to draw people from across the country and all parts of the globe to experience the depth and richness of its color at its source.

Off the northeastern coast of Tokushima Prefecture, in the coastal city of Naruto, Makiko-san has been deepening her relationship with indigo for many years. “My town used to be one of the busiest fishing villages, but now it has become very quiet and increasingly depopulated,” she says. “It is surrounded by the Inland Sea and mountains. I spend most of my time farming, dyeing, and preparing materials for teaching workshops.”

Together with her husband, Martin Tokunaga, she began growing indigo in 2023, in a small field beside her studio. “Every year now we harvest indigo leaves and make our own indigo dye, called sukumo.”

Makiko- and Martin-san during our Thread Caravan trip together.

Sukumo is a composted indigo leaf material produced through a controlled fermentation process. After harvesting, indigo leaves are dried, then piled and repeatedly moistened to encourage fermentation. Over time, with careful turning and temperature control, microbial activity transforms the leaves into sukumo, a stable dye material used in traditional Japanese indigo dyeing. Once fermented, sukumo is often stored for additional time, during which its dyeing properties stabilize and refine. For Makiko, this sukumo-making process takes one month to complete. This patient technique has been practiced in Tokushima for more than 600 years.

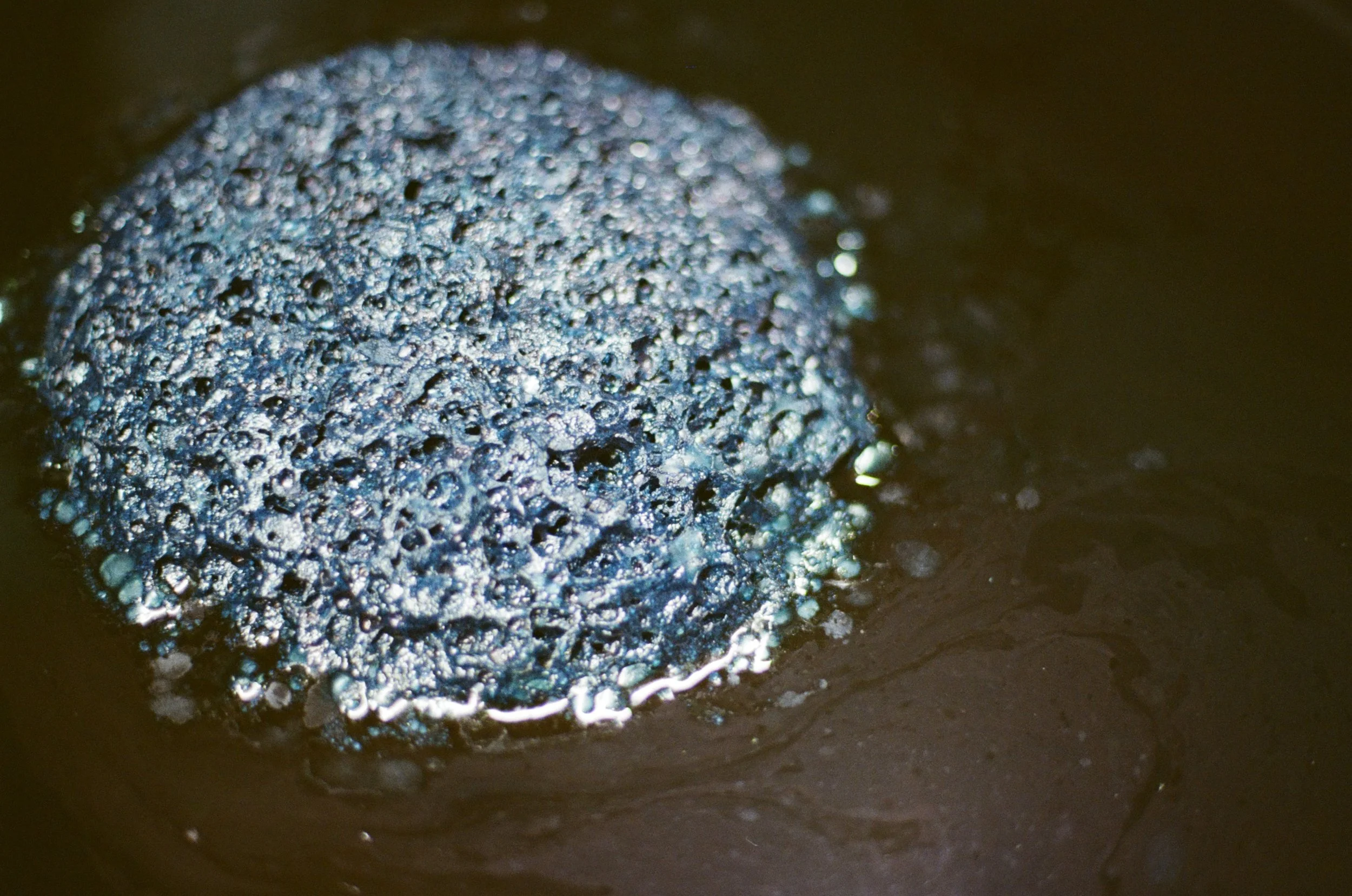

Once the leaves are prepared, the next stage is the preparation of the dye vat. Fermented sukumo is mixed with alkaline water, traditionally made from wood ash.

Microorganisms in the vat create a reduced, low-oxygen environment that converts the indigo into a water-soluble yellow-green form. When cloth is dipped into the vat, it initially emerges yellow-green, then gradually turns blue as it oxidises upon exposure to air.

The indigo flower in one of Makiko-san’s vats.

Makiko-san tends her indigo vat.

Dried indigo leaves and a color sheet hangs in Makiko-san’s studio.

Dyeing with indigo is a majestic process, and Makiko is committed to sharing the magic of Japanese indigo with others. From her studio, she welcomes visitors and introduces them to traditional dyeing practices. One of the primary techniques she teaches is shibori, a resist-dyeing method that creates pattern through binding, folding, or stitching cloth.

Derived from the Japanese verb shiboru, meaning “to wring, squeeze, or press”, shibori encompasses a wide range of techniques. These include kanoko shibori, where small sections of cloth are tightly bound to create dotted or circular patterns; kantano shibori, pioneered by painter turned dyer Motohito Katano (1889-1975), a type of shibori which involves pleating and stitching the cloth; and tatsumaki shibori, in which cloth is wrapped around a pole or cylinder and twisted into a tight spiral. Contemporary artisans continue to push the boundaries of this versatile technique, experimenting and inventing new forms of expression.

Makiko-san hangs indigo-dyed textiles to dry.

Shibori is a slow process that requires a careful hand. For Makiko, however, perfection is not the goal. She embraces the human hand touch and encourages her participants to embrace this too. With the human hand comes error, but also the unexpected surprises which reveal individual art and personal expression .

“What I love most about teaching shibori dyeing is seeing how delighted my participants’ faces are when the see the result of dyeing with indigo - their pure joy and the smile on their faces is a rewarding moment for me,” says Makiko. When students leave her workshop, they carry more than the imprint of blue on their hands, a mark that will eventually fade, they leave with knowledge that has touched something within them, to carry forward a centuries-old technique into new, inspired futures.

One of the Thread Caravan student’s revealing her project after dyeing it in the indigo vats.

Thread Caravan students with finished shibori projects, guided by teacher Makiko-san at her studio.

Photos by Miyu Fukada and Caitlin Garcia-Ahern for Thread Caravan.

Text by Katerina Knight.

More of Makiko-san’s work can be found on her Instagram, IndigoBlue4U.